Certificates and all you wanted to ...

Table of Contents

Intro

First to start with, i am not a mathematician or cryptographer thus when there are errors in this post regarding either subject i am sorry, but please let me know.

With that part aside; certificates we all use them but most people do not have a clue on how they work beyond the statement my traffic is now secure. There is nobody that can listen into my communication, while this is true there is a lot more to it. Lets dive into some history of encryption.

Encryption or maybe even cryptography started around 60BC with the Caesar Cipher Julius Caesar used a simple substitution cipher

(each letter shifted by 3) to send military messages. This is the first recorded use of encryption. In the centuries after that not much happened, small contributions here and there.

This picked up during WW1 and WW2 in which the best known is the Enigma machine.

Before we dive into this subject there are some concepts that are used throughout and might need some explanation;

Key concepts

Cipher or Cypher

A cipher (spelled cipher or cypher, both are correct) is a method of transforming readable information (plaintext) into an unreadable form (ciphertext) — and back again — so that only authorized people can understand it.

In short: Cipher = a recipe for secrecy.

A cipher uses a rule or algorithm and often a key to:

- Encrypt → Convert plaintext → ciphertext

- Decrypt → Convert ciphertext → plaintext

Without the key, the encrypted text should look like meaningless gibberish.

Key/Key size

A key is a piece of information (usually a number or string of bits) that determines how a cipher encrypts and decrypts data.

Think of the cipher as a lock design — and the key as the specific key that fits it.

Without the correct key, you can’t unlock (decrypt) the message — even if you know exactly how the cipher works.

In Simple Terms:

Cipher = the method Key = the secret used by that method

Example (Caesar Cipher): • Cipher = “shift each letter by n places” • Key = n = 3 So, the message “HELLO” → “KHOOR”

If you change the key (e.g., n = 5), you get a completely different result.

Symmetric Encryption

Concept:

- The same key is used to encrypt and decrypt data.

- Both parties must already share the same secret key.

Plaintext --[Key]--> Ciphertext --[Same Key]--> Plaintext

Asymmetric Encryption

Concept:

- Uses a pair of keys:

- Public key → shared openly, used for encryption or verification.

- Private key → kept secret, used for decryption or signing.

Encrypt with Public Key → Only Decryptable with Private Key

Symmetric vs Asymmetric

| Feature | Symmetric Encryption | Asymmetric Encryption |

|---|---|---|

| Keys | Uses one key (same for encryption and decryption) | Uses two keys: a public and a private key |

| Speed | Very fast | Much slower |

| Use Case | Encrypting large amounts of data (files, messages) | Secure key exchange, digital signatures |

| Examples | AES, DES, ChaCha20 | RSA, ECC, Diffie–Hellman |

| Security Basis | Key secrecy | Mathematical problems (factoring, elliptic curves) |

RSA Algorithm

Rivest–Shamir–Adleman) is one of the most famous asymmetric encryption algorithms — it uses two keys: • A public key (for encryption or verifying signatures) • A private key (for decryption or signing)

RSA’s security relies on the difficulty of factoring large numbers.

RSA (Rivest–Shamir–Adleman) is one of the most famous asymmetric encryption algorithms — it uses two keys:

- A public key (for encryption or verifying signatures)

- A private key (for decryption or signing)

Key Generation

RSA’s security relies on the difficulty of factoring large numbers.

Step 1: Choose two large prime numbers

Let’s pick two primes:

\( p \text{ and } q \)

Example: For example: \( p \) = 61, \(q\) = 53

Step 1: Choose two large prime numbers

Let’s pick two primes: \(p \text{ and } q \)

Step 2: Compute \(n = p \times q\)

\(n = 61 \times 53 = 3233\) The number n is used in both the public and private keys.

Step 3: Compute Euler’s Totient Function

\( \varphi(n) = (p - 1)(q - 1) \)

\(\varphi(3233) = 60 \times 52 = 3120 \)

Step 4: Choose a public exponent e

Choose e such that:

\(1 < e < \varphi(n)\)

and

\(\gcd(e, \varphi(n)) = 1\)

Common choices: \(e = 3, 17, 65537\)

Let’s choose \(e = 17\).

Step 5: Compute the private exponent d

d is the modular multiplicative inverse of \(e mod \varphi(n)\):

\(d \times e \equiv 1 \ (\text{mod } \varphi(n))\)

For our example:

\(17 \times d \equiv 1 \ (\text{mod } 3120)\)

Solving gives \(d = 2753.\)

Public and Private Keys

- Public key: \((e, n) = (17, 3233)\)

- Private key: \((d, n) = (2753, 3233)\)

Encryption

To encrypt a message \(M\) (as a number):

\(C = M^e \mod n\)

where \(C\) is the ciphertext.

Example:

\(M = 65\)

\( C = 65^{17} \bmod 3233 = 2790 \)

Decryption

To decrypt: \( M = C^d \mod n \)

\( M = 2790^{2753} \mod 3233 = 65 \)

You get back the original message.

Real-World RSA

- Key sizes today: typically 2048 bits or 4096 bits

- Used in: HTTPS, digital signatures, secure email, etc.

- Usually combined with symmetric encryption: RSA encrypts a random session key, and that key encrypts the actual data (since RSA is slow for large data).

The part that we are interested in starts in the 1970’s. In this period the Diffie-Hellman algorith enabled the Public-key cryptography revolution.

Diffie-Hellman

Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman wrote the paper Diffie–Hellman key exchange in 1976. Below an excerpt from Wikipedia describing the basics working of the algorithm

Diffie–Hellman key exchange establishes a shared secret between two parties that can be used for secret communication for exchanging data over a public network. An analogy illustrates the concept of public key exchange by using colors instead of very large numbers:

The process begins by having the two parties, Alice and Bob, publicly agree on an arbitrary starting color that does not need to be kept secret. In this example, the color is yellow. Each person also selects a secret color that they keep to themselves – in this case, red and cyan. The crucial part of the process is that Alice and Bob each mix their own secret color together with their mutually shared color, resulting in orange-tan and light-blue mixtures respectively, and then publicly exchange the two mixed colors. Finally, each of them mixes the color they received from the partner with their own private color. The result is a final color mixture (yellow-brown in this case) that is identical to their partner’s final color mixture.

If a third party listened to the exchange, they would only know the common color (yellow) and the first mixed colors (orange-tan and light-blue), but it would be very hard for them to find out the final secret color (yellow-brown). Bringing the analogy back to a real-life exchange using large numbers rather than colors, this determination is computationally expensive; it is impossible to compute in a practical amount of time even for modern supercomputers.

Steps of the Protocol

- Public Parameters: Both agree on \(p\) (prime) and \(g\) (generator).

- Private Keys: Each party picks a secret private number: • Alice chooses \(a\) • Bob chooses \(b\)

- Compute Public Keys: Each computes a public value using: \(A = g^a \mod p\) \(B = g^b \mod p\) and exchanges them over the insecure channel.

- Compute Shared Secret: Each party uses the other’s public key with their own private key: \(\text{Alice: } s = B^a \mod p\), \(\text{Bob: } s = A^b \mod p\) Due to the properties of modular exponentiation: \(B^a \mod p = A^b \mod p = g^{ab} \mod p\)

This gives a shared secret s without sending it directly.

Example (Small Numbers)

Note: Real DH uses very large primes (2048-bit or more). This is just an illustrative example.

- Public parameters:

- \(p = 23, g = 5\)

Alice chooses private key \(a = 6\ → \text{computes } A = 5^6 mod 23 = 8\)

Bob chooses private key \(b = 15 → \text{computes } B = 5^15 mod 23 = 19\)

Exchange public keys → Alice gets \(B=19\), Bob gets \(A=8\)

Compute shared secret:

Alice: \(s = 19^6 mod 23 = 2\)

Bob: \(s = 8^15 mod 23 = 2\)

The shared secret is \(2\)

ECDH (Elliptic Curve Diffie–Hellman)

ECDH is the Elliptic Curve variant of Diffie–Hellman. Instead of relying on modular exponentiation with large primes, it relies on elliptic curve mathematics:

- Both parties agree on an elliptic curve and a base point on that curve.

- Each party chooses a private key and computes a public key as a point multiplication of the base point.

- Shared secret is derived from the other party’s public key combined with their private key.

The math ensures the shared secret is identical on both sides, just like DH.

Why ECDH is Preferred Today

- Stronger Security per Key Size

- Traditional DH: Needs very large primes (2048–4096 bits) for security.

- ECDH: Achieves equivalent security with much smaller keys.

- Example: 256-bit ECDH ≈ 3072-bit DH in security strength.

- Better Performance

- Smaller keys → faster computations → less CPU usage.

- Lower bandwidth usage for network protocols.

- Smaller Certificates / Signatures

- Smaller key sizes reduce certificate sizes in TLS, JWT, and other protocols.

- Important for mobile, IoT, and constrained devices.

- Modern Cryptography Standards

- TLS 1.3, Signal, WhatsApp, and many secure messaging apps mandate or prefer ECDH over classical DH.

- NIST, SECG, and other cryptography standards recommend elliptic curves for efficiency and security.

AES

AES is a symmetric-key block cipher, meaning the same key is used for encryption and decryption.

- Block size: 128 bits

- Key sizes: 128, 192, or 256 bits

- Rounds: Depends on key size

- 10 rounds for 128-bit keys

- 12 rounds for 192-bit keys

- 14 rounds for 256-bit keys

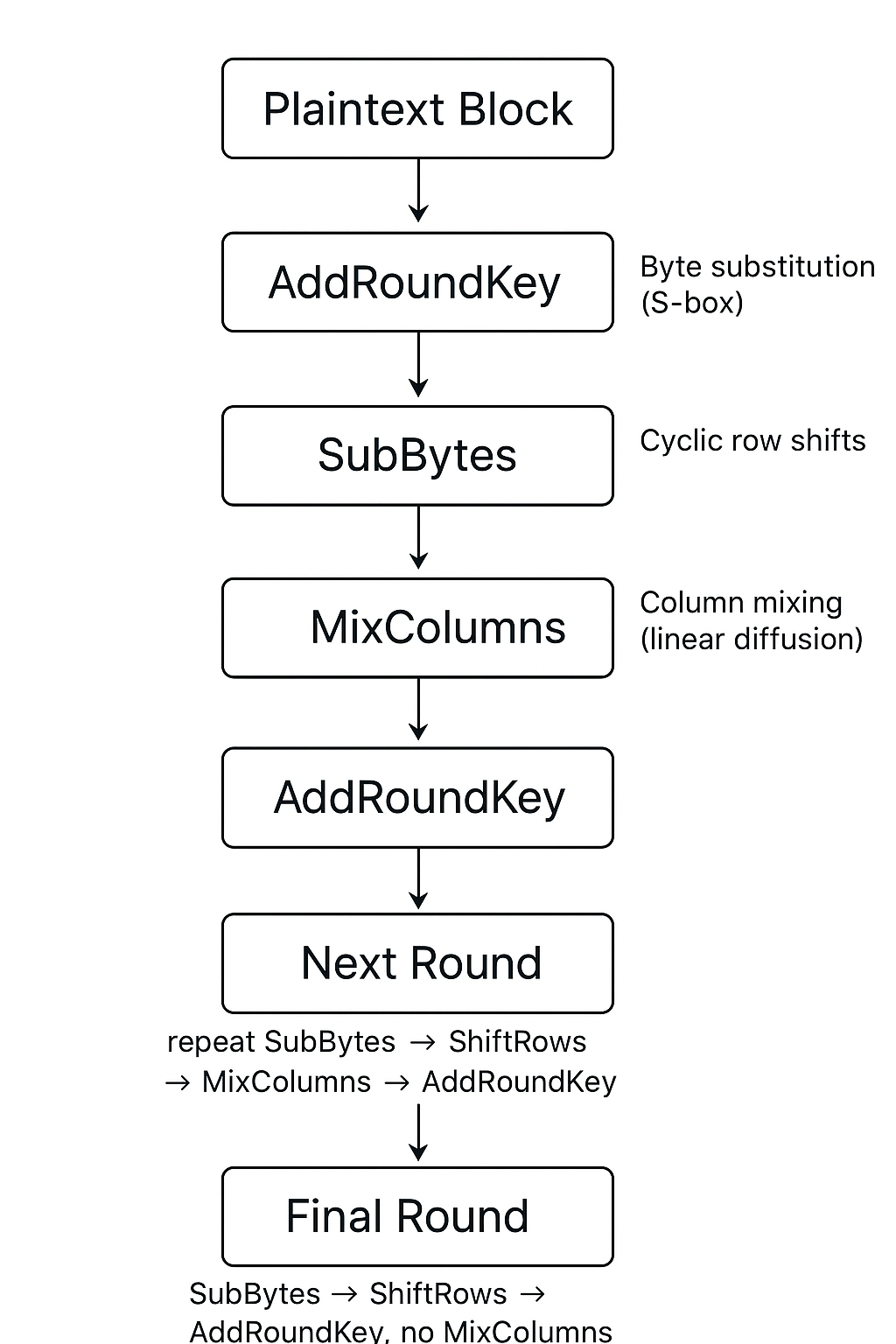

How AES Works

AES operates on a 128-bit block of plaintext, organized as a 4×4 byte matrix called the state.

Each round (except the final one) consists of four steps:

- SubBytes – Byte substitution using a fixed lookup table (S-box) to provide non-linearity.

- ShiftRows – Rows of the state matrix are cyclically shifted to the left to provide diffusion.

- MixColumns – Columns of the state matrix are mixed using a linear transformation for further diffusion.

- AddRoundKey – The state is combined with a round key derived from the main key using XOR.

The final round skips MixColumns.

Key Expansion

- AES uses a key schedule to expand the main key into multiple round keys, one for each round.

- Ensures each round is unique and strengthens security.

Encryption / Decryption

- Encryption: Plaintext → AES rounds → Ciphertext

- Decryption: Ciphertext → Inverse AES rounds → Plaintext

- All operations are reversible using the same key.

Security and Usage

- AES is highly secure when used with strong keys (128-bit or more).

- Widely used in:

- HTTPS / TLS

- VPNs (IPSec, OpenVPN)

- File encryption (BitLocker, VeraCrypt)

- Secure messaging apps

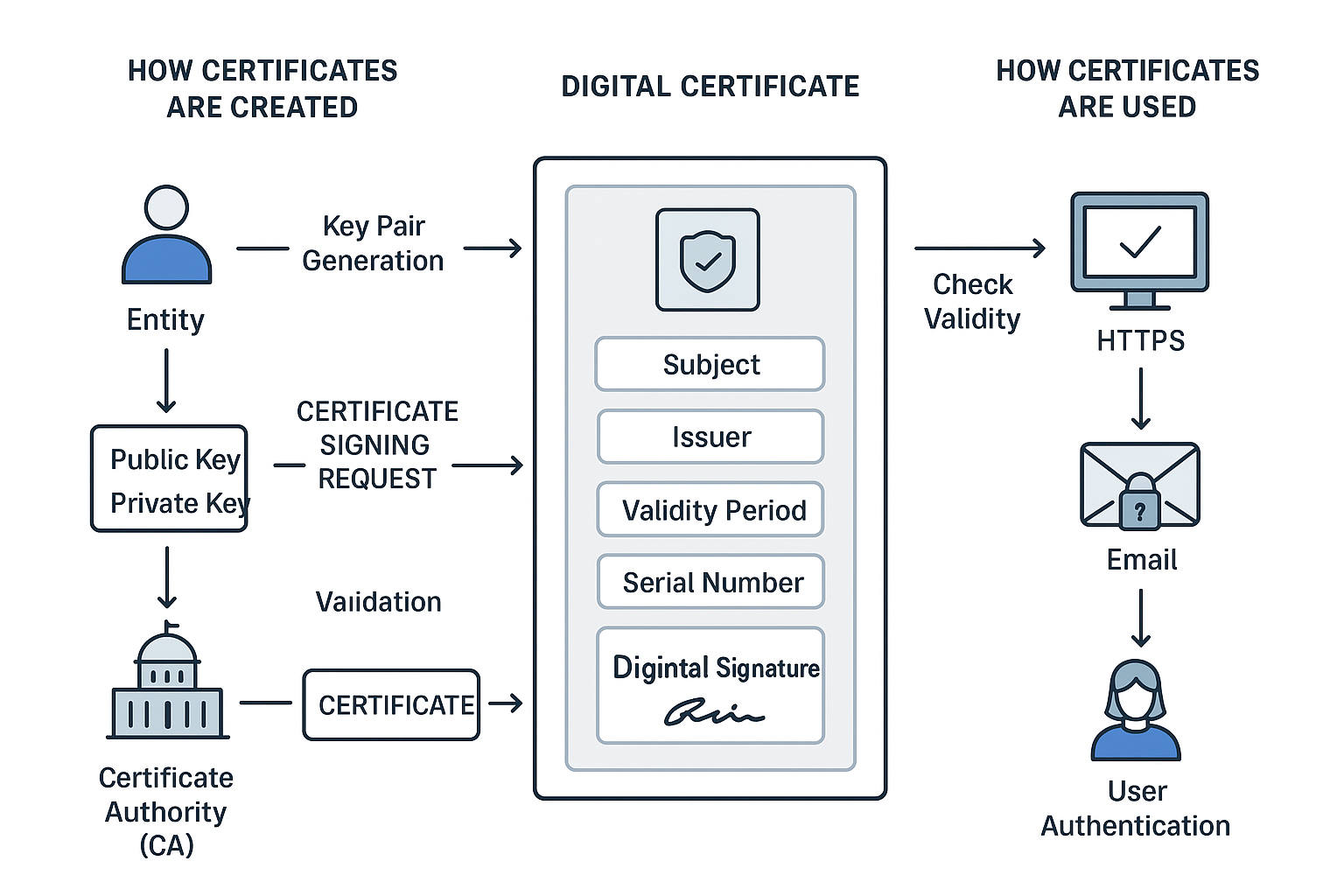

What’s in a certificate?

A digital certificate is like an ID card for a website, person, or device. It contains information that helps verify identity and secure communication. Key components include:

- Subject – Who the certificate is for (e.g., a website’s domain, an individual, or an organization).

- Issuer – The Certificate Authority (CA) that issued the certificate.

- Public Key – Used for encryption and verifying digital signatures.

- Validity Period – Start and end dates of the certificate’s validity.

- Serial Number – A unique identifier for the certificate.

- Signature Algorithm – The cryptographic algorithm used to sign the certificate.

- Digital Signature – The CA’s signature that proves the certificate is authentic.

- Optional Extensions – Extra info like allowed uses (e.g., email encryption, code signing).

How certificates are created

The process generally involves a Public Key Infrastructure (PKI):

- Key Pair Generation: The entity requesting the certificate generates a public key and a private key.

- Certificate Signing Request (CSR): The entity sends the public key along with identity info to a CA in a CSR.

- Validation: The CA verifies the identity of the requester (domain ownership, company identity, etc.).

- Certificate Issuance: The CA creates a certificate containing the entity’s public key, signs it with the CA’s private key, and returns it to the requester.

- Installation: The entity installs the certificate on their server, device, or application.

How certificates are used

- Certificates are mainly used for authentication and encryption:

- Secure Websites (HTTPS):

- When you visit a website, the server sends its certificate.

- Your browser checks the certificate’s validity and verifies it against trusted CAs.

- A secure, encrypted connection is established.

- Email Security (S/MIME):

- Certificates can digitally sign emails to verify the sender.

- They can also encrypt emails so only the intended recipient can read them.

- Software and Code Signing:

- Developers sign software with certificates to prove authenticity and prevent tampering.

- Device or User Authentication:

- Certificates can allow devices or users to securely access networks or systems.